Not every awesome artifact here at MCHS is in the official, accessioned collections. When an organization has existed for 70 years, even the early records of the group have a certain cachet. Our institutional records contain the first book of meeting minutes, scrapbooks of clippings and photographs, files of correspondence, and the like, which are now bona fide historical documents in and of themselves. Here’s the first paragraph of the minutes of our first meeting (transcribed, with additional notes from that meeting, below):

On June 29th some residents of Mont. County, interested in its history, were invited to Glenmore, home of Mrs. Lilly Stone, to form a county branch of the Maryland Historical Society. . . . Mr. J. Barnard Welsh of Rockville spoke of many records and papers in the county that should be cataloged and placed in safe keeping. . . . It was decided to hold a meeting in Bethesda at a later date and every effort be made to contact everyone interested in the history of Montgomery county and invite them to attend the meeting.

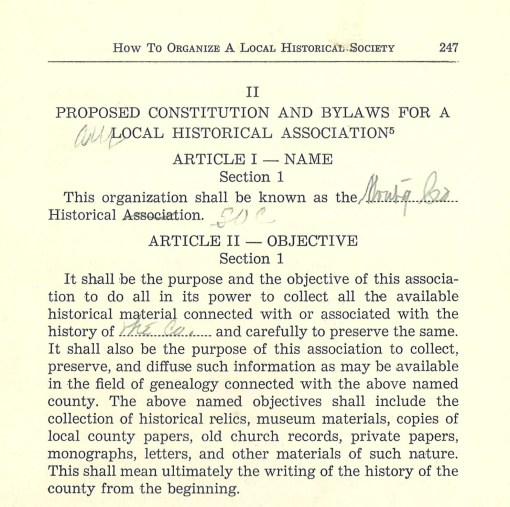

Recently, in sorting through the shelves of museum reference books we’ve accumulated through the years, I came across this handy pamphlet: “How to Organize a Local Historical Society.” I’m a museum-history nerd, so I thought that was interesting: early museum instructions! Then, even better, I realized that this was OUR early museum instruction book. Published in November 1944 – just a few months after our first meeting – by the American Association of State and Local History (AASLH), this pamphlet was the property of Lilly C. Stone, the Montgomery County Historical Society’s founder.

Mrs. Stone made notes throughout the book, highlighting important points, detailing specific members and organizational plans, and filling in the sample “Constitution and Bylaws” with the relevant information. It’s nice to see that we have been a “Society,” not an “Association,” since the beginning (she crossed out “Association” and noted “Soc.”):

Naturally, I was pleased to see some emphasis placed on the proposed duties of the curator:

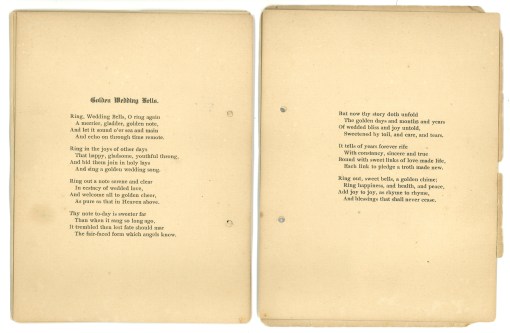

Along with the notebook of handwritten minutes, this annotated pamphlet gives us additional insight into the way early meetings were conducted. I’ve always loved the fact that, as the Recording Secretary noted, most meetings concluded with a musical entertainment; for example, at our fourth meeting (November 22, 1944), “Mrs. Ferdinand Morina sang several numbers accompanied at the piano by Mrs. J. Dunbar Stone. The meeting [then] adjourned and all lingered a short time for refreshments.” Additions in ink to the AASLH’s proposed order of business indicate our early members’ choice to start each meeting with a salute to the flag, and a prayer invocation.

A lot of things have changed since our earliest days – our annual meetings no longer include either prayer or song, take that how you will – but this essential element has remained: We still, as the 1944 pamphlet instructs us, “gather together and carefully preserve and file the historical materials” of our county’s long, diverse history. Lilly Stone might not have envisioned exactly what her Society would become, but I hope she would be pleased to know that seventy years on, the artifacts and records of her county are still being cared for by dedicated volunteers, members, and staff, all of us in some way “residents of Montgomery County, interested in its history.”

. . . And with that, dear readers, I will leave you. This is my final post, as I move on to a new job, and new collections to play – er, work with. These past five years of highlighting our fabulous and varied things have been a pleasure, and I hope you have enjoyed reading my posts as much as I have enjoyed researching and writing them. “A Fine Collection” may continue in the future under new authorship, or perhaps my successor will start his or her own blog (or other platform) for sharing our Historical Society’s great artifacts, photos, and archives; keep an eye on this space, and on our website, for updates. In the meantime, remember to look at all the things around you with interested and analytical eyes. Who made it? Who used it, wore it, played with it, broke it? Who saved it, and why? Artifacts – and the stories and people behind the artifacts – matter!

-Joanna Church

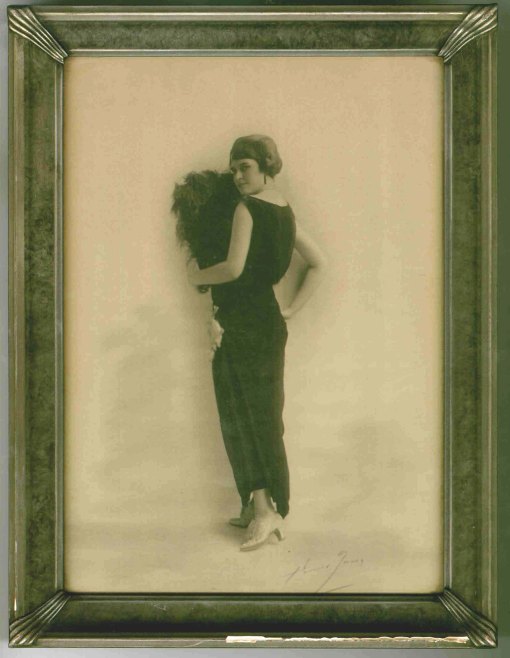

Of course I have to finish with one last Bonus Artifact. Here’s the final image from “The Life of Luther,” 1853, owned by Joseph H. Bradley II of Chevy Chase. The End!

![Three of the cake basket options from the 1896 Marshall Field & Co. catalog, showing the variety of styles. (The bottom basket's description is cut off; it's "satin [finish], bright-cut, 10 1/2 inches high," selling for $5.35.)](https://afinecollection.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/1896-mf-cake-baskets.jpg?w=510&h=407)